ENGL 2105 : Workplace-Based Writing and Research

Questionnaires

How was "gender inequality" defined?

(

link)

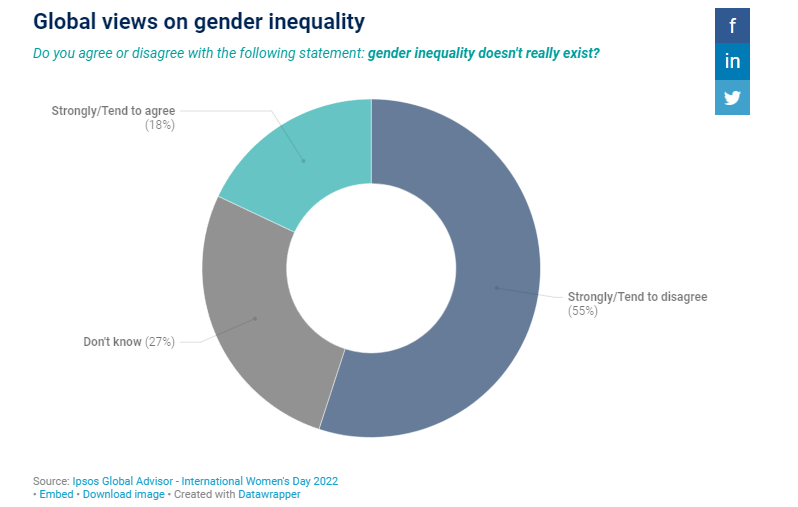

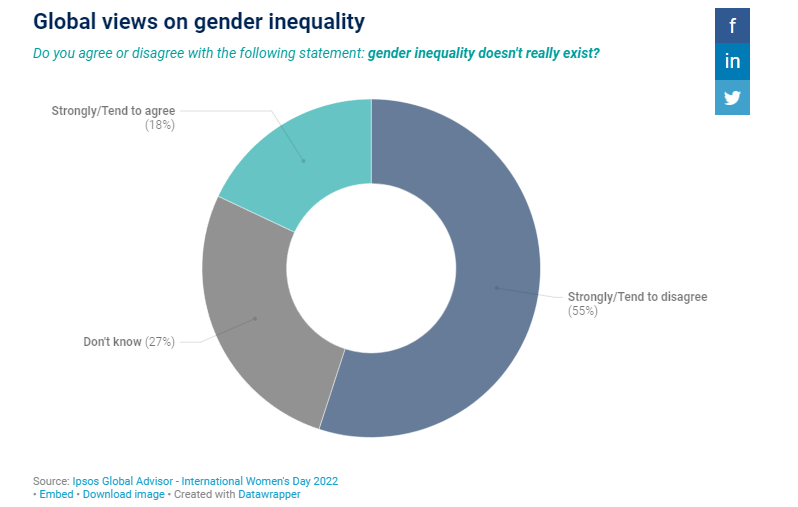

The researchers asked, "Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: gender inequality doesn't really exist." Why "really"? Is that a dog whistle?

- gender inequality doesn't exist

- gender inequality exists

- gender equality doesn't exist

- gender equality exists

Asking the right questions correctly is difficult because the same words can mean different things to different people. "Really" could suggest conspiracy to some people, elicit anger from others, and leave others completely unphased. Does that difference influence the data?.

Questionnaires are the backbone of nearly all forms of human-subjects research. While passive user data gathering may play a greater role in User-Experience research overall, just given the amount and granularity of it, user perception of experience can only be learned from direct questioning. Also, because as we all know, companies are constantly asking for feedback via questionnaires, knowing how to create an informative questionnaire is a marektable skill.

One could easily spend an entire semester on questionnaires alone. What follows is superficial. If you plan on doing any kind of human-subjects research for real, you will need to dig much deeper.

Questioning users is often an ongoing process. Some places keep a database of questions and an archive of past answers. They also keep a list of past respondents and profiles of respondents that might be used to find other respondents. Questionnaires are not a one time thing in most cases, so you should design with as broad a horizon as possible, but of course stay focused on the task at hand.

Because questionnaires can be expensive and time-consuming, it might make sense to think of the practice as a process, where you start by asking a select audience a few questions designed to identify an actionable problem, design what you think is a solution, ask a few more questions to discover if the solution solves the problem without creating new ones, and then create a questionnaire that asks a wider range of users to confirm or deny the efficacy of the solution. In other words, a full-scale questionnaire probably shouldn't be a fishing expedition because you don't want to spend money and time learning nothing useful. You also don't want to burn bridges with your potential informants by having to go back to them for a redo.

Constructing good hypotheses is challenging.

George: What are the key concepts of a hypothesis in general and then specifically in a User Experience context?

ChatGPT: A hypothesis, in general, is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation. It is a fundamental concept in scientific research, forming the basis of experiments designed to verify or falsify it. In any context, a hypothesis typically adheres to these key concepts:

Key Concepts of a Hypothesis

General Concepts

- Testable: Possible to confirm or deny through experiments or observations.

- Falsifiable: Can be disproven if contradictory evidence is found.

- Based on Existing Knowledge: Builds upon previous research and theories.

- Predictive in Nature: Makes predictions about outcomes under specific conditions.

- Specific and Clear: Precise and unambiguous statement of the expected relationship between variables.

- Logical: Consistent with existing knowledge and scientific principles.

Concepts in a User Experience Context

- Focuses on User Behavior and Preferences: Predicts how design changes affect user behavior or satisfaction.

- Informs Design Decisions: Guides design choices and tests design element effectiveness.

- User-Centric: Based on user needs, goals, pain points, or behaviors.

- Driven by Usability and Experience Goals: Relates to usability, engagement, conversion rates, or satisfaction.

- Empirical Testing: Tested via usability testing, surveys, A/B testing, and analytics.

- Iterative: Evolves with increased understanding of user interactions with the product.

Questionnaires require rhetorical thinking

Questionnaires are rhetorical acts, not just the motivated ones designed to gather "evidence" to support a desired outcome but even those that seek to be objective. Who is asked and in what circumstances influences the data. Who is thought to be asking can also influence how a person answers. So you need to answer a number of rhetorical questions (audience, ethos, context) before you start designing a questionnaire.

Assuming you know what question you need answered, the rhetorical questions are along the following lines.

- who are you seeking information from (target population)

- important chartacteristics -- role, knowledge, value

- who are you not seeking information from

- what is a representative sample for your target population

- what is the smallest viable N (number of respondents)

There are also logistical questions that go to context:

- where will you find representatives

- how will you recruit them

- how will you gather the information

- under what circumstances

- their frame of mind

- their perception of you or your agents

-- think "white-coat effect"?

- back when people went to malls, marketers would have people doing high traffic questionnaires and invariably the person with the clipboard was an attractive white-toothed charmer.

- the effect the topic as well as the questions will have on their mood and thus their answers and thus your data

You need to screen potential respondents to find relevant and willing candidates. Once you have a list of useful respondents, you need to run at least one pilot to test the effectiveness of your questionnaire.

Your goal is to ask the least number of questions possible to learn what you need to learn.

Types of questions

Close-ended questions limit what a person can say. The advantage is that you get numbers and numbers are unambiguous, although of course how they relate to a subjective reality or even intersubjective reality (to say nothing of objective reality) depends on how effective the questions themselves were and who you asked (and who answered since not all invited will attend). Don't confuse clarity for accuracy. Close-ended questions are also quicker for a participant to answer because they don't have to compose an answer, just choose one. They don't require thinking, though of course you want to write them in such a way that your participant selects intentionally and meaningfully. You should always consider offering a Not Applicable (NA) and a neutral option so a person isn't forced to contribute data they don't stand by or skip a question leaving you not knowing what the absence of data means (objection, abstention, distraction).

- A/B (limited choice)

- Select one from the following list (limited choice but more options)

- Select all that apply from a list (less limited choice, though still limited unless you add a write-in category)

- True/false/don't know (knowledge)

- Agree/disagree/don't know (opinion)

- Likert Scale (degree of certainty or level of intensity)

Open-ended questions give participants space to say what they think. You get words rather than numbers and you need to be able to code the answers if you plan to generalize. Coding (labeling each item, whether word or phrase or sentence or whatever unit) requires some consistency among the answers. If you can limit an open-ended question to a specific user-type, a persona or a role, and you see similar answers among them, then you might be able to make an argument without further coding.

Open-ended questions can provide subjective insights which makes them great for understanding a single participant. They can also provide useful material (salient quotations) when building personas, but they don't typically generalize very well. So you almost always need a strong context and supporting limited choice questions to build that context out of.

Methods for administering range from clipboard and pencil in a high (relevant) traffic area to a SurveyMonkey type email list to a popup box on a well-trafficked website. Generally speaking the more people respond the better, though if the respondents are the right people you may not need that many. A representative sample can negate the law of large numbers.

Mistakes to avoid

- Skewed sample -- asking only those who will say what you want to hear or those whose answers will not be representative of the general population for any number of reasons or people who don't know what you are trying to find out

- Leading questions -- where the preferred answer is implicit

- Questions based on problematic assumptions -- like a shared context that isn't actually shared

- Carefully scrutinize all your assumptions

- Irrelevant questions -- if an answer doesn't contribute directly to proving or disproving the hypothesis, it's not relevant

- Too many questions -- a person's level of commitment to the project needs to be taken into account, what's in it for them?

- Questions that require a context that hasn't been provided or are answered in a context not inspected

- Complex questions -- two questions presented as one where answering the question amounts to admitting a premise that wasn't specifically asked -- have you stopped binge drinking?

- Questions that have overlapping responses -- options should be mutually exclusive. If A and B are or can be interpreted as insufficiently dis-similar, the respondent will be confused

- Double-barreled questions -- two separate questions expressed as one -- if there is an "and" in the question it is probably two questions

- Questions that lead to more questions that can't be followed up on -- don't ask, "Are you willing to participate in a follow-up interview" if you know you won't follow-up.

- Asking for opinions when objective measures are possible -- unless you want to know what people think to contrast with what is real

- Asking for opinions that any respondent would not have a considered opinion about -- encouraging fabulation

- Order effects, unintended influence over responses by putting respondent into a frame of mind with one question that then influences their answers to the next. You can control for this by scrambling the question order before presenting them, so different respondents are asked the same questions but in a different order. Of course, if some questions are intentionally clustered, you need to keep them together

- Failing to take respondents' feelings and attitudes into account. If you ask a potentially embarrassing question, people may lie to save face. People lie to themselves too, so if you ask a question that they might be inclined to answer aspirationally rather than realistically, you should try to ask another that will control for that. Another potential problem is that people who want to please or impress will say whatever the questionnaire appears to want. As well as the opposite. And so on.

- Making the respondents uneasy or upset or harried or otherwise in a counter-productive frame of mind or doing so intentionally to get desired outcome or knowing they will be and taking advantage of that

- Vague quantifiers (often, usually, frequently, rarely)

- Loaded language, dog whistles

- Jargon or technical terms that some respondents might not know

- Double negatives

- Idioms that non-native speakers might not know

- Absolute terms like "always" and "never" exclude nuance and might force a person to overstate their feelings or ignore the question and leave an uninterpretable gap

- Asking more or less the same question in two different ways when the variant doesn't illuminate the original

- Asking a question that likely contradicts an answer to another one without meaning to do so -- like when you want to know if a person might not fully understand something or when you are trying to catch someone lying

- Asking Y/N questions when a range of answers is plausible

- Don't pressure your respondent to say what you want to hear

- Not giving a "don't know" or "not applicable" option, thus forcing a respondent to add data that isn't accurate or leave a gap in the data that isn't interpretable

- Offering a range where the difference among options is ambiguous or poorly calibrated -- "Please rate each of the following statements on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 indicates strongly disagree and 5 strongly agree." What do 2, 3, and 4 mean?

- Inconsistent scaling -- don't ask for a range from 1 to 5 and then from 1 to 10 at another time

- Ignore the mode of administration -- online is not the same as face-to-face

These mistakes are easier to make than they may seem. Pilot test a questionnaire with several different types of respondents before you ship it.

Typical parts of the questionnaire process

- Hypothesis -- statement that will prove true or false based on the data generated by the questionnaire

- Planning -- identify population, determine N, recruit (might need small preliminary questionnaire for this)

- Population -- all possible users

- Population, Sample -- those you try to reach

- Population, Sample N -- users who responded to a questionnaire. Indicates reliability.

- Population, Representative Sample -- statistically significant number of respondents. You need to account for anomalies, special groups, self-selected samples, and so on.

- Design -- questions, order, what kind of data comes back and how to visualize and use it

- Questionnaire:

- Preamble -- orient the respondent to the questionnaire: why the research, what the process, what's in it for them, how data will be stored, for how long, and who will have access

- Consent -- we don't' plan to publish or distribute, so we don't need IRB, but you always need informed consent

- Questionnaire

- Thank you --

- Follow up -- what happens next for you, for them, if anything

- Work with data

- Decide on next steps